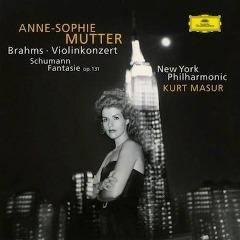

Brahms - Violinkonzert Schumann – Fantasie (1997)

Brahms - Violinkonzert Schumann – Fantasie (1997)

1. Brahms: Violin Concerto in D, Op.77 - 1. Allegro non troppo 22:57 2. Brahms: Violin Concerto in D, Op.77 - 2. Adagio 9:24 3. Brahms: Violin Concerto in D, Op.77 - 3. Allegro giocoso, ma non troppo vivace - Poco più presto 7:54 4. Schumann: Fantasy for Violin and Orchestra in C major op.131 - Moderato semplice ma espressivo 13:20 Anne-Sophie Mutter – Violin New York Philharmonic Kurt Masur - Director

In his book of the 1914 St. Petersburg chess tournament, Dr. Siegbert Tarrasch, bitter adversary of world champion Emanuel Lasker, generously conceded that Lasker's magnificent play in that event (he won it in a blistering finish) had made him worth his huge fee. Norman Lebrecht has recently documented the fees paid to artists like Anne-Sophie Mutter. From the evidence of her recording of the Brahms concerto with the New York Philharmonic, her playing, like Lasker's, has made her worth it!

In 1978, it was natural to wonder what would happen when the youthful purity and grace of Mutter's Mozart Third Concerto (DG 2531 049, now available on DG 429 814-2) gave way to more mature, though not necessarily more insightful, musicianship. Works like Brahms's Concerto provide a good chance to assess how freely her musical impulses continue to flow. And the good news is that there is still a rich vein to be tapped. Compassing her expressive ends less through mannered portamentos (some of these are, in fact, a bit ungainly) than through firmly controlled dynamics, articulation, and vibrato, she has developed more as a classical than as a romantic violinist—but one nevertheless as capable of flamboyant gesture as Stern or Oistrakh. Although her earlier recordings suggested she might, Mutter still does not possess the strong personality of Szigeti, whose 1928 performance of Brahms's Concerto with Sir Hamilton Harty and the Halle Orchestra was exceptionally tough (although she comes close in the finale), or of Kreisler, whose 1927 reading with Blech is at once magisterial and sweet-tempered; still in all, hers is as strong-minded and individual as violin playing comes nowadays.

Joseph Hellmesberger branded Brahms's as a concerto against the violin (remember Sarasate's displeasure at having to stand about while the oboe played the "only good melody" in the slow movement), and violinists fall into two main camps: those who regret that Joseph Joachim disturbed the flow of Brahms's pianistically conceived ideas, and those who regret that Brahms took so few of Joachim's suggestions. Mutter, apparently in the first camp, plays a concerto solo, not a symphonic obbligato, and the engineers have supported her point of view. But the prominence they have accorded her is not altogether inappropriate: compared to Mutter's angular strength, the orchestral statement, although richly textured, seems soft edged. Despite its merits, however, her second recording of the Brahms reveals little that wasn't compassed in her 1982 account with Karajan and his smoothly powerful orchestral juggernaut, now available on DG 415 565-2, and even lacks the brash tonal edge of that reading's visceral finale. But it's still propulsive and virtuosic; and what it may have lost in precocious freshness, it has gained in greater overall coherence—a mark, after all, of musical maturity. In its combination of virtuosity and control—and its close miking—her performance recalls another—Leonid Kogan's with the Philharmonia Orchestra conducted by Kiril Kondrashin (Angel 35690 and S-35690, reissued on Seraphim S-60059). A comparison is unavoidable with the maturing but a bit younger Ginette Neveu's 1949 live recording with Antal Dorati (Music & Arts CD-837), in which David K. Nelson (Fanfare 18:4, pp. 124-26) found evidence that her playing was becoming "more rough-edged and probing (more like Szigeti)"—more like Szigeti, in fact, than Szigeti himself dared to sound! In contrast, Mutter has steel-wooled some of the rough surfaces that made her earlier recording approach Neveu's from 1949.

Schumann's infrequently heard Fantasy is familiar principally from recordings by German violinists Aida Stücki (Vox PL 7680. Mutter studied with Stikki at the Winterthur Conservatory after the death of her first teacher—was that how she became aware of the work?) and Suzanne Lautenbacher (the latter now available in VoxBox CDX-5027. Kogan and Valéry Klimov also recorded it, but with piano). More extroverted than Schumann's concerto, the Fantasy's violinistic brilliance alone might have been expected to keep it alive; and Mutter's straightforward virtuosity, hardly inappropriate in such a work, helps to prop up its slenderer musical content. The pairing, although not especially generous at 53:35, is an apt one, the Fantasy serving as an extended encore with a strong connection to the main program. Mutter's is first-rate Brahms that could be strongly recommended even without any discmate, but with Schumann's Fantasy, it's all the more desirable— not quite Lasker in St. Petersburg 1914, but worth its price nonetheless. ---Robert Maxham, FANFARE [3/1998], arkivmusic.com

download (mp3 @320 kbs):

uploaded yandex 4shared mega solidfiles zalivalka cloudmailru filecloudio oboom