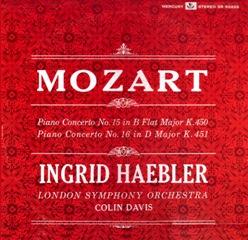

Mozart - Piano Concerto No. 15 & No.16 (Ingrid Haebler) [1965]

Mozart - Piano Concerto No. 15 & No.16 (Ingrid Haebler) [1965]

Piano Concerto No. 15, K.450 • Klavierkonzert Nr. 15, KV 450 4 I Allegro 5 II Andante 6 III Allegro Piano Concerto No. 16, K.451 • Klavierkonzert Nr. 16, KV 451 1 I Allegro 2 II Andante 3 III Allegro Di Molto Ingrid Haebler – piano London Symphony Orchestra Colin Davis – conductor

The leap in artistic growth between Mozart's piano concertos of 1782 (K. 413-5) and the series composed in 1784 (K. 449-451, 453, 456, 459) was one of the greatest in the composer's brief career. Thus the Piano Concerto No. 14 in E flat major, K. 449, is sometimes regarded as Mozart's first mature work in the genre. Five weeks after the composition of K. 449 Mozart completed a strikingly different work in the Concerto in B flat major, K. 450. Mozart's entry for the piece in his "List of All My Works" is dated March 15, 1784. The Piano Concerto in D major, K. 451, would follow only seven days later. Mozart composed both these works for his own use in public concerts, describing them to his father as "concertos to make you sweat." Not surprisingly, then, the part for the soloist is far more virtuosic than in K. 449, which was composed for one of Mozart's students. Furthermore, the writing for the wind instruments, in K. 450 in particular, is more involved and advanced than in any of Mozart's earlier piano concertos. Scored for piano, strings, paired oboes, bassoons, and horns, with a single flute in the finale, K. 450 features a woodwind section more deeply integrated into the total texture than in K. 449.

Opening with a tune reminiscent of Mozart's Salzburg-era serenades, the Allegro throughout is marked by unusual orchestration. Once the piano part begins, the soloist dominates the movement, with the orchestra occasionally reduced to providing only punctuation. Indeed, the soloist's initial lengthy passage contains no references to the opening ritornello. It would be wrong to call the central solo span a development section, for absolutely no development occurs in this continuous wash of flashy, bravura piano figurations. There is, however, a "recapitulation" containing themes omitted by the piano during its first episode and the central section.

In 3/8 time, the E flat major Andante consists of a theme with two variations and a coda. The two-part theme modulates to the dominant (B flat major) at the midpoint. Mozart's variations are decorative; no fundamental changes occur in the melodies.

B flat major is generally considered one of Mozart's "happy" keys, and the Allegro finale does nothing to alter this conception. A rondo in 6/8 time, the movement is filled with flashy piano passages and hand crossings. Mozart varies the returns of the rondo section, altering the order of the melodies and extending them, and thus making it seem as though we are hearing a chain of variations. As in the first movement, the piano part is technically difficult, designed to highlight the performer: Mozart. ---John Palmer, Rovi

Contemporary records show that Mozart gave no fewer than 22 public performances between February 26 and April 3, 1784. In this period, it should come as no surprise to discover that he chose to return to a grand and brilliant format in the composition of his Piano Concerto No. 16 in D major, K. 451. As with its nearest predecessor in the same key of D major, Concerto No. 5, K. 175, the concerto includes parts in its orchestration for trumpets and drums, always emblematic of a pronounced celebratory and public style in Mozart concertos. (An even earlier D major Concerto, listed as K. 40, the third of Mozart's 27 piano concertos, was in fact an arrangement of sonata movements by Honauer, Eckard, and in the finale, C.P.E. Bach.) No. 16 is, however, an altogether deeper work, both more passionate and vital in character, more structurally masterful, and with a slow movement of remarkable intellectual substance.

The first movement (Allegro) opens with a typically Mozartean march-like figure, evoking a rhythmic formula virtually identical to that which opened Concerto No. 13 in C, K. 415. Mozart was to employ the same solution again in a number of his subsequent piano concertos, notably Nos. 18 in B flat, K. 456, and 19 in F, K. 459. Mozart's solitary Piano Concerto in G, K. 453, differs only slightly in that it features a trill on the second note, though the generally purposeful demeanor of its opening is the same. The most arresting characteristic of the D major Concerto, K. 451, is its near-symphonic robustness and ambitious sense of scale throughout each of its three movements, and in this work, Mozart undoubtedly achieved a significant advance in unifying both symphonic and concerto genres in a new, all-embracing creative unity. Indeed, it may well be reasonable to suggest that the "modern" Classical piano concerto was born on March 22, 1784, the completion date which appears at the head of the manuscript. Although Mozart probably played the work himself soon afterwards, the copy he later sent to his sister contained one passage of the Andante in fragmentary form. He, therefore, sent her a substitute passage in richer harmonies, although on many occasions, Mozart's copies of concertos he played himself seem to have been at best sketchy, including just the bare outlines of themes upon which he would extemporize in performance. Listeners new to the work will find the bracing final rondo (marked Allegro di molto) especially powerful and dramatic, offering an affirmative summary of one of Mozart's most innovative middle-period piano concertos. --- Michael Jameson, Rovi

download (mp3 @320 kbs):

uploaded yandex 4shared mega mediafire zalivalka cloudmailru oboom uplea