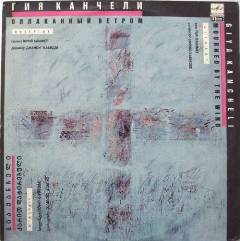

Giya Kancheli - Mourned By The Wind - Bright Sorrow (1991)

Giya Kancheli - Mourned By The Wind - Bright Sorrow (1991)

Mourned by the Wind, liturgy for solo viola & orchestra 1 I. Molto Largo 11:09 2 II. Allegro Moderato. Largo Molto 8:10 3 III. Larghetto 9:12 4 IV. Andante Maestoso. Molto Tranquillo 15:28 5. Bright Sorrow: Cantata For Chorus & Orchestra 30:52 Yuri Bashmet – viola State Symphony Orchestra Of Georgia Jansug Kakhidze – conductor Boy's Choir Of The Moscow Choral School Konstantin Savochkin, Valentin Konstandi - boy singer Victor Popov – chorus master

In May 1984, one of Kancheli's best friends, the Georgian music critic Givi Ordzhonikidze, died. Four months later, Dr. Ulrich Eckhardt, the director of the West Berlin Festival, commissioned for performance at the festival a work from Kancheli to be dedicated to Ordzhonikidze's memory. The result, the four-movement liturgy Mourned by the Wind, was not completed until the autumn of 1988; its first performance had to wait yet another two years, until September 9, 1990, when violist Yuri Bashmet and the Orchestra of the Leningrad Kirov Theatre under Valery Gergiev played the work in West Berlin.

Kancheli wrote of Mourned by the Wind: "Probably a page, a blank page containing a faint trace of dried tears could tell us everything or almost everything about the contents of the Liturgy..." The work was one of Kancheli's quietest, most melancholic and static compositions to date. It begins with a loud dissonant chord in the piano, which opens the Molto largo first movement. The viola enters, rocking sadly between two notes, accompanied by spacious chords from the orchestra. The tone is overall one of resignation, with an occasional more intense outburst. Martial sounds from the brass and percussion, long tones from the viola, and a big Shostakovich-like climax mark the second movement, Allegro moderato. The third movement, Larghetto, returns to a mournful tone, with delicate harpsichord and tuned percussion decorating long, sustained tones from the soloist and orchestra. In the final movement, Andante maestoso, the dark voice of the viola contrasts with a forceful idea in the orchestra that recurs several times. More diatonic material seems to offer some solace, but the pervading gloom remains, only somewhat dispelled by a peaceful coda.

On completing the composition, Kancheli wrote a letter to his friend Ordzhonikidze, now dead for four years: "It is unbearably difficult without you...Many still have to realize that by defending us, you were asserting your faith, your truth, your music...We need you now, when there is a demand for thinkers, preachers, fighters. A demand for genuine leaders...So much that is unexpected, new, exciting is happening before our eyes...To the limit of my capabilities I have attempted to express in the Liturgy my personal attitude to such a personality. To the ideal that was, for me, embodied in this person." ---Chris Morrison, Rovi

Bright Sorrow again draws from the bottomless well of lamentation which is the ex-USSR composer’s special curse and privilege. This was a commission from the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra and the publishers Peters Edition, and it bears the dedication “To children, the victims of war”. Hence the choice of two boy soloists (superb singing here from Ian Ford and Oliver Hayes), to intone phrases from Goethe, Shakespeare, Pushkin and the contemporary Georgian poet Galaktion Tabidze, symbolizing the innocent victims of the last world war addressing themselves to the present-day generation and reminding us of our responsibilities to the future. The title, incidentally, reflects Goethe’s image of “Nacht wird heller” (“Night becomes brighter”), so Light Sorrow (as the disc has it) is a potentially misleading translation.

The soloists sing only slow, fragmented lines, “like an ocean contained in a drop of water” according to the composer, and marvellously conveying the fragility of innocence. These fragments are tied together (possibly unconsciously) by head-motifs from Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms and the famous Russian revolutionary lament Vi zhertvoyu pali (“You fell as a victim”) so beloved of Shostakovich and Soviet film-music composers, while the overall concept of polyglot texting and the fusion of pacifism and religiosity reflects a conscious admiration for Britten’s War Requiem.

The second half of the work seems to be gaining strength and optimism, but these are soon obliterated, leaving behind only a heart-broken crippled waltz, and the final climax recalls the vociferous protest near the end of the Sixth Symphony. Indeed if anyone has been wondering, as I have, where the best, or at least the most epic Kancheli went to after the Sixth Symphony (since even the Seventh Symphony feels rather like a half-hearted afterthought), here is surely the answer. ---gramophone.co.uk

download (mp3 @320 kbs):

yandex 4shared mega mediafire cloudmailru uplea ge.tt