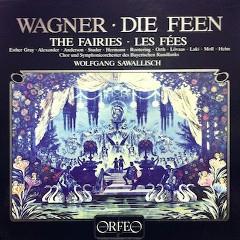

Richard Wagner - Die Feen (The Fairies) (1983)

Richard Wagner - Die Feen (The Fairies) (1983)

CD 1 01. Ouverture 02. Feengarten Introduktion (Chor der Feen) 03. Rezitativ (Farzana, Zemina) – Chor der Geister und Feen 04. Wilde Ein.de mit Felsen Szene und Rezitativ (Gunther, Morald, Gernot) – Gerno 05. Arie (Arindal) 06. Rezitativ (Gernot, Arindal) 07. Romanze (Gernot) 08. Quartet (Arindal, Gunther, Gernot, Morald) Finale I 09. Rezitativ (Arindal) 10. Feengarten mit gl.nzendem Palast Cavatina (Ada) 11. Rezitativ und Duet (Ada, Arindal) 12. Szene (Ensemble und Chor) CD 2 01. Introduktion (Chor der Krieger und des Volkes, Lora) 02. Arie (Lora) – Szene (Bote, Lora, Chor) 03. Chor und Terzett (Lora, Arindal, Morald) 04. Rezitativ (Gernot, Gunther) – Duett (Drolla, Gernot) 05. Rezitativ (Ada, Farzana, Zemina) 06. Szene und Arie (Ada) 07. Finale II (Chor des Volkes und der Krieger, Lora, Drolla, Arindal, Gunther) CD 3 01. Introduktion (Chor, Morald, Lora, Drolla, Gunther, Gernot) 02. Szene und Arie (Arindal) 03. Szene (Stimmen Adas und Gromas; Farzana, Zemina) 04. Terzett (Arindal, Farzana, Zemina) 05. Szene (Chor der Erdgeister, Arindal, Farzana, Zemina, Gromas Stimme, Chor von 06. Schlussszene (Feenk.nig, Arinda, Chor der Feen und Geister) Der Feenkönig – Kurt Moll (bass) Ada – Linda Esther Gray (soprano) Farzana – Kari Lövaas (soprano) Zemina – Krisztina Laki (soprano) Arindal – John Alexander (tenor) Lora – June Anderson (soprano) Morald – Roland Hermann (baritone) Gernot – Jan-Hendrik Rootering (bass) Drolla – Cheryl Studer (soprano) Gunther – Norbert Orth (tenor) Harald – Karl Helm (bass) Ein Bote – Fried Lenz Die Stimme Des Zauberers Groma – Roland Bracht Chor Des Bayrischen Rundfunks Symphonieorchester Des Bayrischen Rundfunks Conductor – Wolfgang Sawallisch

Wagner was 20 years old when he composed Die Feen (The Fairies), and it is worth a listen. Here’s a bit of Weber (Oberon and Freischütz); a hint of Mozart (Zauberflöte); an effect from Beethoven’s Fidelio. Choruses are plentiful and impressive, and there is coloratura writing for the soloists ( remember, Wagner was enamored of Bellini at this point in his life). The fantastic plot has elements of the Orpheus myth in Act 3, when our tenor hero, Arindal, with harp accompaniment, brings his soprano wife, Ada, back to life through the magic of music. When he originally meets her, she is in the form of a doe; he, a mortal prince, is permitted into her world of shape-shifting fairies, providing he not ask her who she is for eight years. He cannot help himself and she is taken from him. The opera itself is concerned with them returning to one another. Shades of Lohengrin; shades of immortality through music (Wagner himself). Oh yes, and redemption through love.

The plot is sick with incantations and transformations and is better off left alone. Some of the music winds up in Rienzi (bits in the overture; parts of the first-act finale) and there are hints of other operas as well. The work is just shy of three hours; Wagner revised it in the following year but it was never performed in his lifetime (its premiere was in 1888, five years after his death). Despite some exciting ensemble work sprinkled throughout, lengthy periods of exclamation and explanation wear it down. One listen should be enough. Wagner gave the score to King Ludwig of Bavaria when the latter became his patron; it was later given to Hitler and is believed to have perished with him in his bunker in 1945. ---Robert Levine, classicstoday.com

On the evidence of Die Feen, Richard Wagner at twenty was already a dramatist. His score is startling in its freedom from convention. The standard view of Wagner's development is that he moved from early conformity — adherence to the formulaic aria structure and tunefulness of Romantic-era opera — to a more fluid, open, unpredictable style more dependent on text. But this precocious 1833 work finds him already breaking traditional molds and — while skillful in details such as orchestration — not especially adept at, or interested in, sustained melody such as we find in the early 1840s in Holländer or even Rienzi.

He was also juggling multiple influences in Die Feen — Gluck, Mozart, Beethoven, Weber and, not least, Heinrich August Marschner (1795–1861), a composer who affected both Wagner's choice of fantastical subject matter and his irregular, through-composed musical structure. While we recognize a cavatina here and a cabaletta there, as models or points of departure, their realization is intermittent, sometimes camouflaged and distorted. Weber-style climaxes with multiple scalar passages are broken by sustained, anarchic high notes that unsettle the harmony and the period style. Often the promise of song gives way to dramatic events and reactions; the goal seems always to be excitement. The prevailing vocal mode is accompanied recitative, restless in tonality and especially tempo, interrupted rather than supported by instrumental gestures, and somewhat overheated in manner even for this lurid libretto of repeated moral tests (anticipating Lohengrin) and revolving-door metamorphoses. The composer wrote his own text, based on plays by Carlo Gozzi.

But all is not sturm und drang. Another arresting innovation is the mostly skillful arioso style, blending recitative and melody. (There's even comic relief in the Act II reunion of two lovers long separated by war, a Papageno–Papagena style exercise.) Young Wagner also maintains interest with his instrumentation, often with flute coloring, which is sometimes said to derive from Marschner as well. The chorus gets opportunities for rousing finales (though never very extensive) and brief interaction, sometimes cross-cut by recitative. One fascinating moment comes in the elaborate a cappella passage in Act III for five principals and chorus, a fine example of vocal counterpoint that extends without accompaniment for thirty-six measures. Arindal's Act III music includes two winning solos, a brief scene of delusion ("Hallo! Lasst alle Hunde los") and then, following the sudden recovery of his senses, a lyrical appeal to the gods, with harp accompaniment, to spare Ada, the heroine, who has been (temporarily) turned to stone.

One mark of continuity with the mature Wagner is the taxing vocal writing, which requires the services of a dramatic tenor and two stalwart sopranos of considerable range. (An often brilliant performance recorded under Wolfgang Sawallisch in 1983 had John Alexander, June Anderson and Cheryl Studer in the cast.) ---David J. Baker, operanews.com

download (mp3 @320 kbs):

yandex mediafire ulozto bayfiles